LAS MUJERES DEL MOVIMIENTO BAUHAUS: HISTORIA PERDIDA /THE WOMEN OF THE BAUHAUS MOVEMENT: MISSING HISTORY

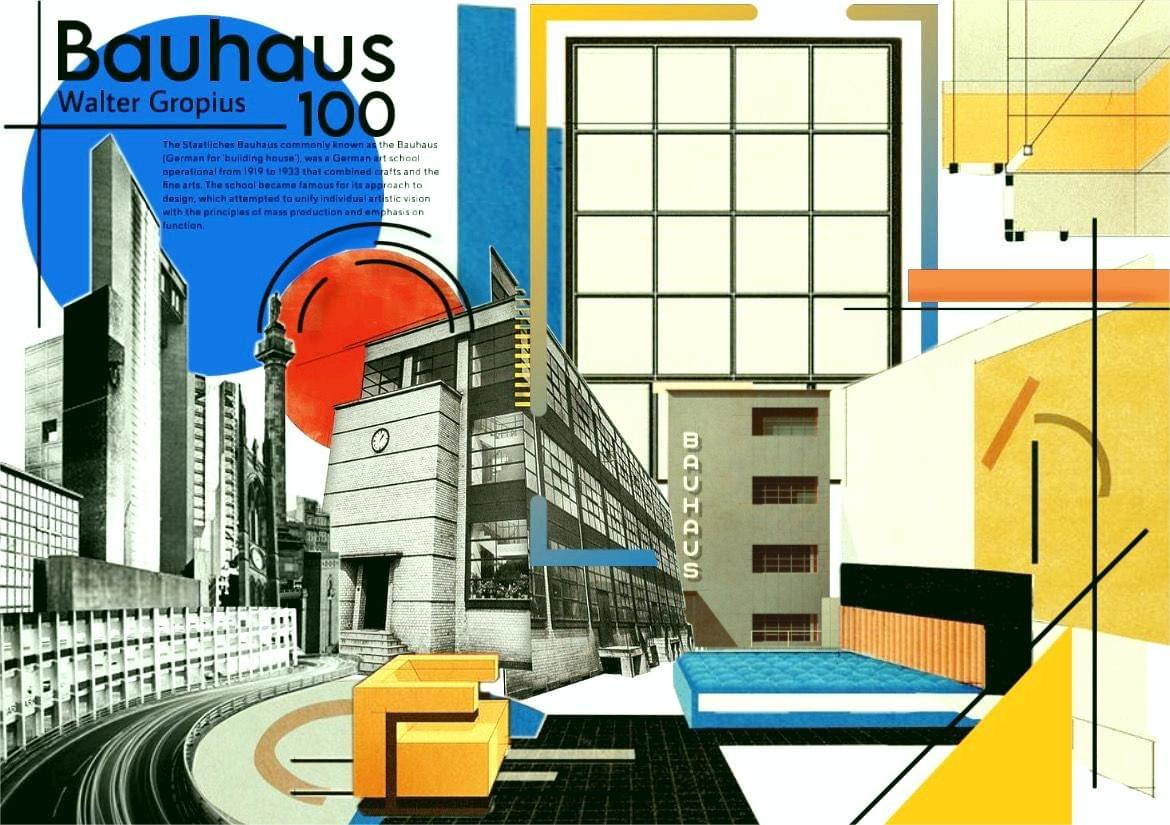

La Bauhaus, fundada en 1919 por el arquitecto Walter Gropius en Alemania, revolucionó el diseño y la arquitectura, fusionando arte y artesanía de manera profunda. A menudo se celebra por su estética minimalista, formas funcionales y énfasis en la simplicidad, pero esta narrativa con frecuencia eclipsa las contribuciones de las mujeres que jugaron papeles vitales en dar forma a este movimiento icónico. Comprender la intrincada historia de la Bauhaus requiere abordar las imprecisiones en su narrativa y reconocer las contribuciones significativas, pero a menudo ignoradas, de las mujeres.

The Bauhaus, founded in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius in Germany, revolutionized design and architecture, merging art and craftsmanship in profound ways. It is often celebrated for its minimalist aesthetic, functional forms, and emphasis on simplicity, but this narrative frequently overshadows the contributions of women who played vital roles in shaping this iconic movement. Understanding the intricate history of Bauhaus requires addressing the inaccuracies in its narrative and acknowledging women's significant yet often overlooked contributions.

La Fundación de la Bauhaus / The Founding of Bauhaus

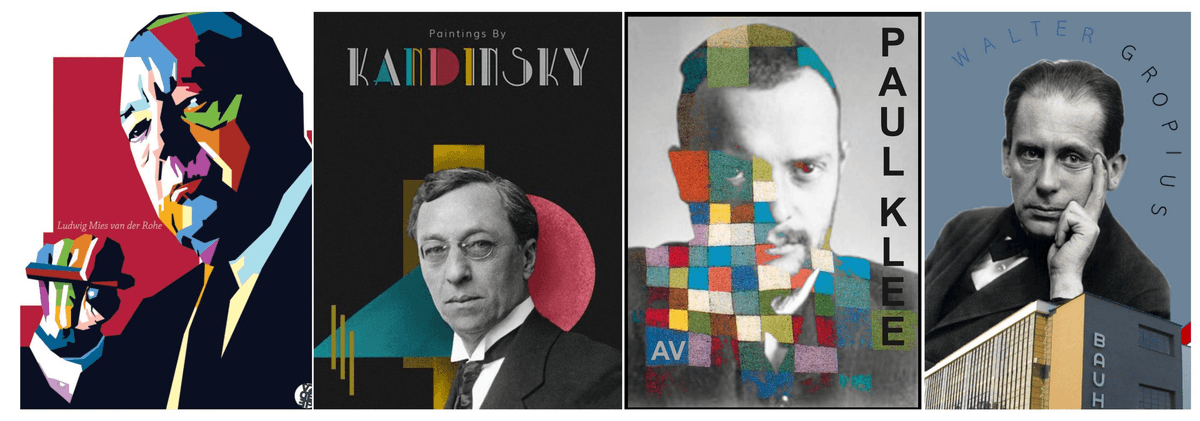

La escuela Bauhaus pretendía tender un puente entre la producción industrial y las artes, combinando una variedad de disciplinas: arquitectura, diseño gráfico, diseño de muebles y más. Su influencia se extiende mucho más allá de su tiempo, estableciendo el marco para los principios del diseño modernista. Sin embargo, las historias tradicionales destacan predominantemente figuras masculinas como Gropius, Mies van der Rohe y Paul Klee, mientras que descuidan los papeles esenciales desempeñados por las mujeres.

The Bauhaus school aimed to bridge the gap between industrial production and the arts, combining a variety of disciplines—architecture, graphic design, furniture design, and more. Its influence extends well beyond its time, setting the framework for modernist design principles. However, traditional histories predominantly highlight male figures such as Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Paul Klee while neglecting the essential roles played by women.

MUJERES no pueden ver en tres dimensiones / WOMEN can’t see in three dimensions...

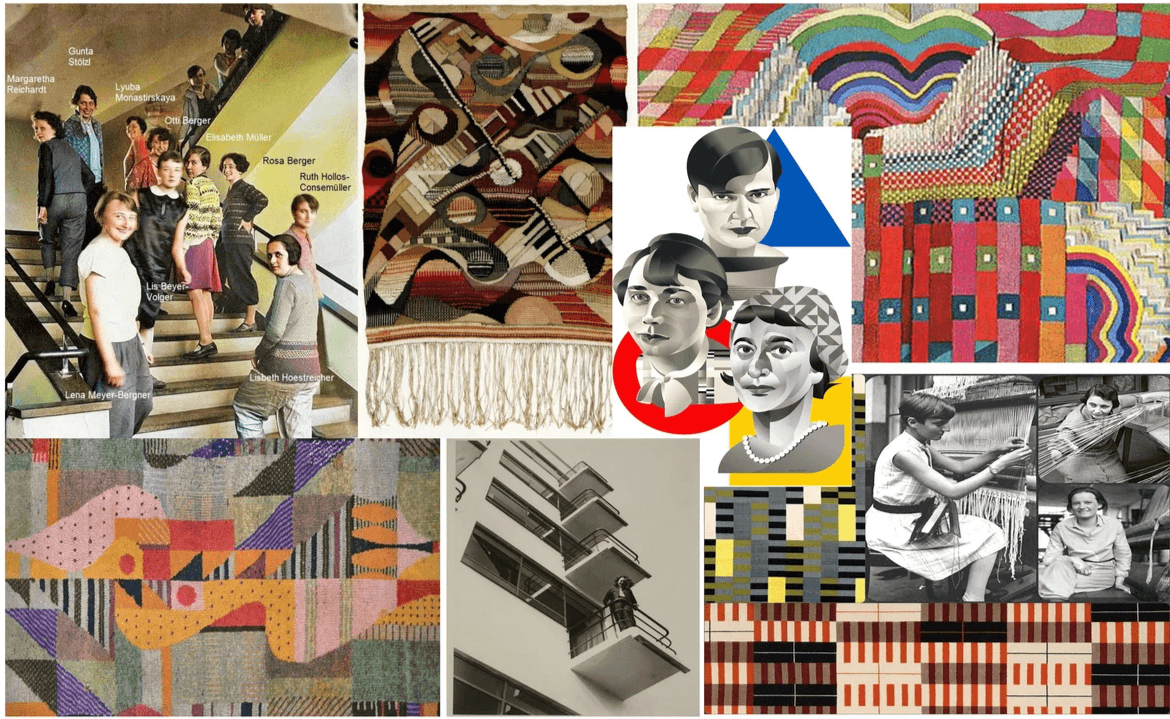

Relegadas a la llamada 'clase de las mujeres', las artistas transformaron el arte no amado de tejer en su propia forma de arte. Haciendo las cosas a su manera, descubrieron nuevos tipos de textiles. Las mujeres utilizaron las famosas formas y teorías del color de Bauhaus en su arte textil. En atrevidos experimentos de color, Se crearon formas radicalmente nuevas utilizando hilados teñidos a mano combinados en técnicas de tejido muy complejas. Los artistas utilizaron sus telas como lienzos de pintura.

Las telas creadas tuvieron un enorme éxito. Las mujeres realmente revolucionaron el diseño textil. Ya no se hablaba de ello como un simple pasatiempo, ya que el maestro de la Bauhaus Oskar Schlemmer lo había descartado.

En toda la historia de la Bauhaus, el taller textil fue sin duda uno de los estudios más exitosos. Hicieron la mayor cantidad de dinero, vendieron mucho, exhibieron mucho y produjeron mucho, pero todo eso no fue bien recibido por los hombres de la Bauhaus.

Relegated to the so-called ‘women's class’, the female artists turned the unloved craft of weaving into their own art form. Doing things their way, they discovered new types of textiles. The women used the famous forms and color theories of Bauhaus in their textile art. In bold color experiments, radically new forms were created using hand-dyed yarns combined in highly complex weaving techniques. The artists used their fabrics like painting canvases.

The fabrics created were enormously successful. The women really revolutionized textile design. There was no more talk of it simply being a pastime, as Bauhaus master Oskar Schlemmer had dismissed it.

In the entire history of the Bauhaus, the textile workshop was undoubtedlyone of the most successful studios. They made the most money, they sold a lot, exhibited a lot, and produced a lot, but all that was not well-received by the Bauhaus men.

Se decía que el arte es un talento, y las mujeres no lo tenían. Para Paul Klee, el arte tenía que ver con la genialidad, que las mujeres no poseían. Cuando se trataba de bellas artes, no reconocía a las mujeres. Wassily Kandinsky sentía lo mismo. Era un negocio de hombres, relacionado con el intelecto, y el negocio de las mujeres era solo sobre la maternidad. 'La promesa de igualdad de derechos en el trabajo fue rota por el argumento de que las mujeres no pueden ver en tres dimensiones y trabajar mejor con superficies planas.' Las mujeres que llegaron a la Bauhaus con el sueño de convertirse en arquitectas, pintoras y escultoras se encontraron repentinamente relegadas al telar y a una habilidad considerada no un arte sino una artesanía.

It was said that art is a talent, and women didn't have it. To Paul Klee, art had to do with genius, which women didn’t possess. When it came to fine art, he didn’t recognize women. Wassily Kandinsky felt the same. It was a man's business, to do with the intellect, and women’s business was only about motherhood. 'The promise of equal rights in work was broken by the argument that women can’t see in three dimensions and work better with flat surfaces.' Women who came to the Bauhaus with the dream of becoming architects, painters, and sculptors suddenly found themselves relegated to the loom, and to a skill considered not an art but a handicraft.

Estas mujeres no solo enriquecieron el currículo de la Bauhaus, sino que también introdujeron sus propios paradigmas, combinando artesanía con estética modernista. A pesar de su labor pionera, muchos relatos históricos minimizan o omiten por completo sus contribuciones, relegándolas con frecuencia a la sombra de sus homólogos masculinos.

Por ejemplo, cuando las estudiantes de sexo femenino o los maestros logran el éxito, sus homólogos masculinos a menudo se sienten amenazados, lo que conduce a un entorno que podría socavar los logros de la mujer. La cultura sutil pero generalizada de la envidia limitaba el reconocimiento de las contribuciones de las mujeres y sofocaba sus avances dentro del campo.

These women not only enriched the Bauhaus curriculum but also introduced their own paradigms, blending craft with modernist aesthetics. Despite their groundbreaking work, many historical accounts minimize or entirely omit their contributions, often relegating them to the shadows of their male counterparts.

For instance, when female students or masters achieved success, their male counterparts often felt threatened, leading to an environment that could undermine women's accomplishments. The subtle yet pervasive culture of envy limited the recognition of women's contributions and stifled their advancements within the field.

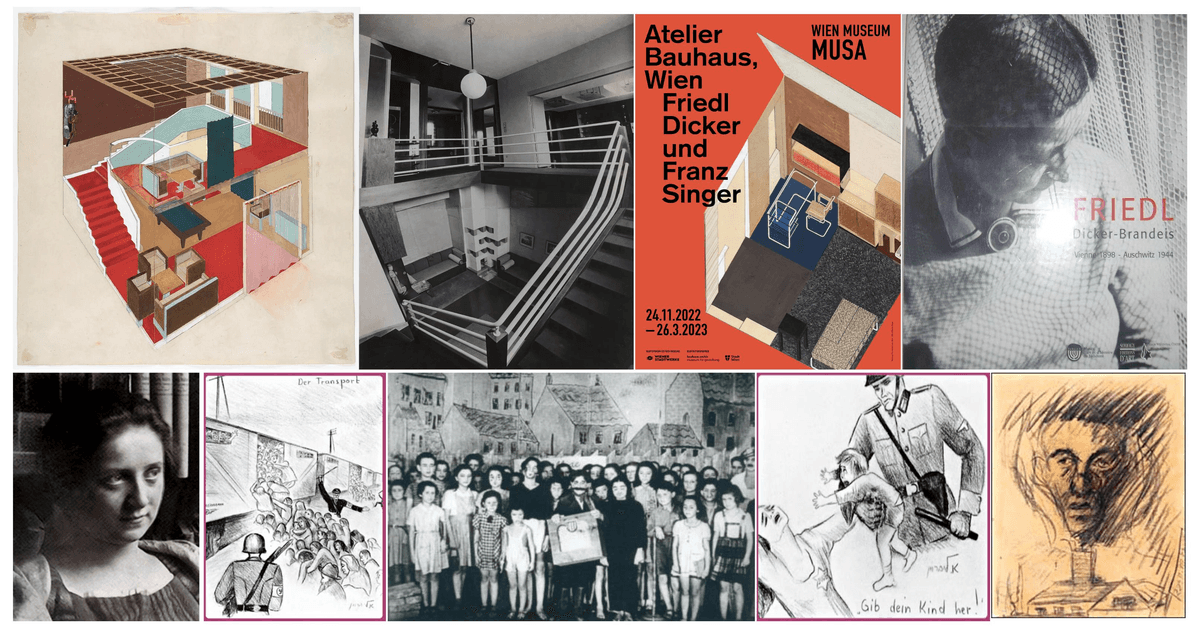

La polifacética Friedl Dicker se negó a estar vinculada a un único taller. Disfrutaba de un nivel excepcionalmente alto de libertad en la institución. Dicker incluso conquistó los talleres de hombres.

En 1922, Friedl Dicker fue el primer estudiante de la Bauhaus en diseñar una casa con techo plano. Fue verdaderamente una pionera en tantas cosas que hizo, es imposible enumerarlas todas. La Bauhaus pronto se volvió demasiado pequeña para Friedl Dicker. Después de proyectos en Dresde, Berlín y Viena, Dicker fundó un estudio de arquitectura en Viena junto con Franz Singer donde diseñó la arquitectura y el mobiliario Bauhaus para una clientela adinerada. Cualquiera que siguiera las tendencias tenía una pieza de Singer-Dicker en su casa.

En septiembre de 1942, Friedl fue deportada al gueto de Theresienstadt. Aquí Dicker aún logró organizar cursos de dibujo para niños . Cuando su marido es deportado de Terezin, ella se ofrece como voluntaria para el siguiente transporte, a Auschwitz. En el campo Friedl Dicker-Brandeis fue asesinado en una cámara de gas en 1944 a la edad de 46 años. Su marido, Pavel Brandeis, sobrevivió al Holocausto. Antes de ser deportado a Auschwitz, Friedl llenó dos maletas con unos 4.500 dibujos de niños y los puso en un lugar secreto; después de la guerra fueron recuperados y entregados al Museo Judío de Praga.

The multifaceted Friedl Dicker refused to be linked to a single workshop. She enjoyed an exceptionally high level of freedom in the institution. Dicker even conquered the men’s workshops.

In 1922, Friedl Dicker was the first Bauhaus student to design a flat-roofed house. She was truly a pioneer in so many things she did, it is impossible to list them all. Bauhaus soon became too small for Friedl Dicker. After projects in Dresden, Berlin and Vienna, Dicker founded an architecture studio in Vienna together with Franz Singer where he designed the Bauhaus architecture and furniture for a wealthy clientele. Anyone who followed the trends had a Singer-Dicker piece in their house.

In September 1942, Friedl was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Here she Dicker still managed to organize drawing courses for children . When her husband is deported from Terezin, she volunteers for the next transport, to Auschwitz. In the camp, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was murdered in a gas chamber in 1944 at the age of 46. Her husband, Pavel Brandeis, survived the Holocaust. Before being deported to Auschwitz, Friedl filled two suitcases with about 4,500 children's drawings and put them in a secret place; after the war, they were recovered and handed over to the Jewish Museum in Prague.

Perspectivas modernas sobre la Bauhaus / Modern Perspectives on Bauhaus

Hoy en día, los estudiosos y entusiastas están revisitando cada vez más la historia de la Bauhaus, esforzándose por iluminar las contribuciones de las mujeres y desafiar las narrativas centradas en el hombre que históricamente han dominado. Exposiciones, publicaciones y debates se centran ahora activamente en estas figuras olvidadas, reconociendo las dimensiones multifacéticas del movimiento Bauhaus.

La reevaluación histórica no solo honra la memoria de mujeres como Albers, Dicker y Stölzl, sino que también fomenta una comprensión más amplia de los procesos creativos en la Bauhaus. Al implementar una lente de género, podemos apreciar el espíritu innovador de esta era mientras reconocemos el trabajo a menudo invisible de las mujeres.

Today, scholars and enthusiasts are increasingly revisiting Bauhaus history, striving to illuminate the contributions of women and challenge the male-centric narratives that have historically dominated. Exhibitions, publications, and discussions now actively focus on these overlooked figures, recognizing the multifaceted dimensions of the Bauhaus movement.

Historical reevaluation not only honors the memory of women like Albers, Dicker & Stölzl but also encourages a broader understanding of the creative processes at Bauhaus. By implementing a gendered lens, we can appreciate the innovative spirit of this era while recognizing the often invisible labor of women.